Chaotic Marriages – Indian Law

[ad_1]

Written by Sanjay Raman Sinha

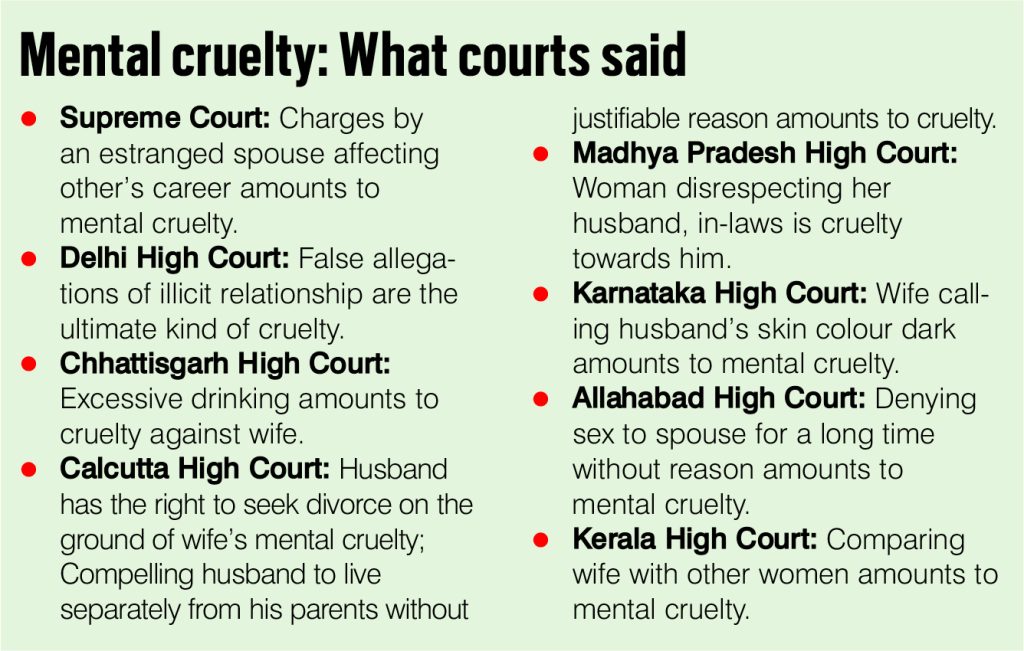

A recent flurry of judgments and observations has shed light on cruelty in marriage. Many marriages have fallen apart after the husband faced the brunt of mental or physical violence.

The Delhi High Court recently noted that the wife’s “continued insistence” to live separately from her husband’s family without justified reason “can only be described as an act of cruelty”. The court ordered the dissolution of the couple’s marriage on the grounds of “cruelty and desertion” under the Hindu Marriage Act. In another case, the Delhi High Court ended a decade-old marriage, saying that there was no law that gave a husband the right to beat and torture his wife just because they were married. The Supreme Court also noted in a recent ruling that keeping parties together despite the irreparable breakdown of the marriage amounts to cruelty on both sides.

Marital discord festers like an ulcer and manifests itself in various ways, mental toughness being one of them. Physical forms of cruelty are readily apparent, but mental cruelty is more subtle and unbearable. It corrupts the psyche of the aggrieved party and leaves the marital relationship in a deplorable state.

Acknowledging its harmful effects, the Hindu Marriage Act 1955 Section 13(1)(a) allows both a wife and a husband to file for divorce on the grounds that their husbands subjected them to cruelty after marriage.

The oath says: “Any marriage entered into, whether before or after the commencement of this Act, may, upon application by husband or wife, be dissolved by decree of divorce on the ground that the other party (a) ‘has treated the petitioner roughly after the celebration of the marriage’.” .

Cruelty here includes both physical and mental. Mental cruelty is a criminal offense under international patent law. Article 498a of the Islamic Penal Code penalizes a husband or any relative of his who subjects a woman to cruelty. Cruelty includes actions that would cause a woman to commit suicide, cause her serious injury, or endanger her life. This clause also includes harassing the woman or any of her relatives to satisfy any unlawful demand for money, property or any other valuables. This section was specifically introduced in 1983 to check the risk of dowry-related violence and other forms of spousal violence against women.

There is no similar provision in the law that provides for cruelty against men by their wives. The Supreme Court has stressed that, in many cases, men are equally vulnerable to marriage abuse as their female counterparts. The husband can file for divorce on this basis. The Court has also established the test by which a person’s behavior amounts to cruelty. It held that the decision had to be made not only on the basis of whether the act would appear cruel to a person of normal sensibilities, but mainly on the effect it would have on the aggrieved spouse who appeared in court. This is because what may be cruel to one person may not be cruel to another.

So the cruelty is conditional. The person alleging cruelty only has to prove that the spouse’s behavior created a fear that continuing to live with that person would be harmful to him or her. Mental cruelty is difficult to define and can include the following situations: humiliating a spouse in front of his/her family and friends, terminating a pregnancy without the husband’s consent, making false allegations against the spouse, and denying a physical relationship without proper evidence. The reason, the constant demand for money, the aggressive behavior of the husband, and so on. The law recognizes this cruelty as a reason for the husband to seek divorce as well.

Incidentally, except for Uttar Pradesh, no other state has made any amendment in Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act so that cruelty is grounds for divorce. In 1976, Parliament under the Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act amended Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act to make cruelty also a ground for divorce. This happened after the 1976 amendment, which allowed divorce and judicial separation. In this case, the wife wrote a letter to her husband’s employer containing false allegations. The court held that this action constituted cruelty under the Hindu Marriage Act 1955. “The cruelty is physical as well as mental. If the allegations are false, they will cause psychological distress to the accused.

Under this amendment, Section 10 of the Hindu Marriage Act has also been amended in such a way that instead of giving clear grounds for judicial separation, a scheme has been drafted so that a petition for judicial separation can be filed on any of the grounds for divorce specified in sub-paragraph (1) of Section 13. It is Then, the same grounds are now available for judicial separation as well as for divorce. After the 1976 amendment, the cause of cruelty in judicial separation as well as divorce became: “(1) Treat petitioner harshly after the celebration of marriage.”

The scheme liberalized provisions related to judicial separation and divorce. Now it is not necessary to prove that the defendant has repeatedly dealt with the petitioner harshly. Further, the petitioner also may not prove that he was treated with such severity as to cause a reasonable apprehension in his mind that living with the other party would be harmful to him.

It is now clear, under the amended law, that mental cruelty must be of such a nature that the parties cannot reasonably expect to live together. It need not be shown that mental cruelty caused danger to the health, limbs or life of the petitioner. Mental cruelty now carries the same weight as physical abuse, audio and visual evidence, and witness testimonies.

At a time when marriages are under stress due to mental and physical cruelty committed by one spouse towards the other, the Domestic Violence Act, which punishes men for harassment, has become a tool of persecution on false grounds used maliciously by wives. This was stated in no uncertain terms by the Kolkata High Court recently.

In another case, the Calcutta High Court issued a slew of directives, including no automatic arrest of defendants in domestic violence cases. The court ordered police officers to be instructed “not to automatically make an arrest upon registration of a case under Section 498-A of the International Penal Code, but to be satisfied of the necessity of arrest under the above-mentioned criteria flowing from Article 41 of the Penal Code.” This proves the other side where penal provisions which aim to protect women are used maliciously by them.

Courts and legislators have now recognized this fact and have made provisions for legal remedies. But this is primarily a social distress, and legal action is considered a last resort, often at the expense of marriage.

[ad_2]

Source link